Hi there friends.

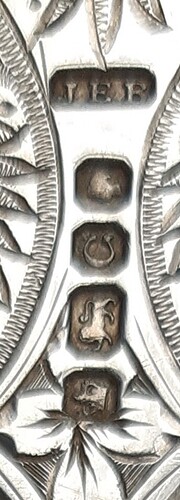

I might be guilty of partiality towards the spoons I own. I happen to consider this J E Bingham spoon to be beautiful indeed, in more respects than one. Please see the pics.

Some might have an altogether different opinion. I respect that.

Length: 17,9 cm. Bowl width: 3,9 cm. Weight: 43 g. Maker’s mark JEB = John Edward Bingham. Date letter G = 1874. Crown assay office = Sheffield. That’s now if I have assessed the spoon correctly; however, everything seems to tally up nicely. (Phil knows I have in the past erred greatly!)

I have a question bugging me, and I ask your help:

The main attraction this spoon has for me (besides its lovely proportions and balanced feel in the hand) lies in the intricate but pleasing pattern impressed upon it. I am wondering exactly how this was done by the smith Bingham. I’m sure the pattern was not bright-cut by hand into the silver. It’s too finely executed and regular for that to be true. Am I right when I think it was rather some kind of die stamping? But how that is possible taking all the curves of the bowl into consideration! My question is: how could they have done it?

Regards

Jan

If you were going to invent bright cut work today it would probably be done using pattern systems first devised by the lacemakers but it was a decorative system for silverware invented when light was low and created by candles, mirrors and lustres and labor was both skilled and cheap.

Channel Island silversmiths had a problem in the Victorian era; it was cheaper to buy silver coming out of the large shops in the UK, including Sheffield than to make it themselves. The implementation of the rolling mill and stamping machines for both cutlery and hollowware created this inequity and the Islanders just didn’t have the capital to buy the rolling mills.

Elsewhere on this site I have posted examples of fiddle pattern cutlery made in London by Elizabeth Eaton – daughter of prolific maker William and overstamped by a Channel Island smith.

Exactly why the Channel Island buyers preferred their flatware bright cut to plain I don’t know but it wasn’t until 1897 Guernsey got its first public power generators and that was only for street lights.

Now I don’t know your spoon ever went to the group of Islands offshore St Malo, France but it is highly likely it was made for export to there and yes, it’s done freehand out of a marked pattern possibly in Sheffield and possibly in the Islands. The decorative designs are created by making a series of short cuts into the metal, using a polished engraving tool that causes the exposed surfaces to reflect light and give an impression of brightness.

The technique was most frequently used in England and countries influenced by the work of English silversmiths during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It is sometimes used in diamond settings to make the stones appear larger.

Like cut glass it really had to be done by hand and cut rather than stamped out of a mound. Those sharp edges to the cuts are what throws the light back at the diner.

Sometimes you see it done on holloware in combination with embossing or hammering out the silver.

It first appeared with frequency on English silver in the rococo period heralded into London by the Huguenot smiths fleeing France. Porringers, salt and spice boxes and shakers appear with regularity at auction and are sold today at prices dwarfing those we achieved 20 years ago.

Your spoon is unusual for its overall dual-sided decoration and for the lack of love shown to it. And by love I mean that ultimate enemy of all silver the diligent butler with his silvo-saturated polishing rag.

CRWW

Guildhall Antiques

CRWW, thank you very much for your kind response. I must admit I had some doubts about my posting when no quick reply was forthcoming. You have raised many points about the spoon in question and I must verify that I understood all.

First of all you imply that the design on my spoon is in fact bright-cut. So it was brought about by hand, and in its current condition (through lack of love) it is a marvelous and clear example of the engraver’s art. To me that engraver must be a master at the art, because I ran that work through a ‘fine-tooth comb’ with my 10X magnifier and I stand astounded.

Secondly, you advise that the spoon was made in the smooth state by the maker and then let go, and the later engraving is an outside work. You suggest that the Channel Island buyers might have been involved. So Sir Bingham probably had nothing to do with the engraving, but he surely did make the spoon, him being a silversmith in the employ of Walker & Hall, years before he took over the management.

Thirdly, whoever the engraver was, he did not get to “make his mark” on the spoon, so his identity remains unknown. (By the way, I have an identical fork by the same maker, same engraving, same year, same everything, even down to the initials in the cartouche. Whether they are a once-only set of two, or part of a larger service, I’ll never know.)

If you feel I have misunderstood anything, please let me know. With my thanks once again.

Regards

Jan

You have nailed the essence of it.

As luck would have it a rather good friend of mine is a direct descendant of the Walker Hall dynasty, or perhaps I should say dynasties and I tackled her on the single issue of where one or many more of the 1500 employees would have been tasked with bright cut work to order or if it would have been “sent out”. It appears that the rigidity of the silversmith’s union at the time and the attractiveness of subcontract prices especially abroad would have made the latter more likely.

I then took the liberty of making a fairly detailed enquiry from another friend at OCAD here in Toronto as to process, tools used, modern pattern systems either digital or old school and how that differs from systems employed 150 years ago.

Taking the first matter first, in-house or contract out, in-house work would have been subject to two problems; coarsening the system to make it operate in the the then nascent union environment and the softening of cutline work by the buffing women then employed on piecework.

Then all tools would have been hand or arm powered, unless it was in house and use of steam powered engraving tools was employed. Apparently it is perfectly possible to tell if a cutting or hand graver is employed or something that operates rather like a dentist drill is employed and from the photos you provided yours appears to be hand cut and therefore probably done on contract.

So much for history now comes the interesting bit and it accounts for much of the delay in answering your "unless you tell me to the contrary I will assume XY&Z is correct " comment, a technique I sometimes employ in the lower courts on sunny afternoons when nobody’s paying too close attention to counsel shenanigans.

Since there seems to be little demand for. bright cut work on a mass scale as in a long set of cutlery today, I cannot find anybody in the industry using a computer program to guide a cutting tool to complete the engraving work. Basically to achieve today in silver what a Jacquard loom achieved in the lace and brocade industry 221 years ago.

So I got a hold of my friends in the digital world to design a program to run a machine to chisel spoons into surface patterns. The problem is simple, and this was a problem Hargreaves faced with his looms in the cotton industry slightly earlier, to make the mechanization of a hand craft commercially viable you need to complete work laterally and if it is spoons, then complete say 20 spoons all at once. Otherwise you run into the same problem the Frenchman who first milled coins for the English Queen Elizabeth in 1562 faced; it’s easier and more profitable to do it by hand and hammer!

Elizabeth, who had little use for Frenchman since one was sent for to cut of her mother’s head with a broad sword of Damascus steel, imprisoned him in the Tower where the mint and his mill machine was set up and shortly thereafter executed him on the recommendation of Spymaster Walsingham.

So there you have it, your instinct was right, it’s just the labor costs were cheap and suppressed by the pending mechanization and the skills were plentiful and again suppressed this time by the closed-shop unions of the day.

I am grateful for your efforts in heading me down this metaphysical rabbit hole but like Alice I find I cannot fit through the door, having taken the pill to reach the tabletop key to open it!

Chris, your latest reply drew my admiration in at least three ways. One, you have shown your zeal in going after the truth and in the process given us here in the forum much enlightenment regarding the silversmithing trade back in the day. Two: as a writer of sort I was totally won over by your eloquence and I smiled all the time while reading it. Three (and this might be the most important for me), you have not hesitated to share your knowledge with me and those of the forum reading this post. I can only say thank you very much. Your replies are worth a second and even third read.

Regards

Jan

As an afterthought, I guessed that some readers might have wanted to see the matching fork mentioned earlier on. Please see the pics.

So, noting that both the fork and the spoon has the same monogram, one would not imagine that the whole service it belonged to would have been thus bright-cut. Alternatively (and drawing on what Guildhall had written) these two items as well as the rest of the service might have been produced ‘in the smooth’ and monogrammed to the original owner. Then, perhaps, this fork and spoon had later been removed from the set and sent out to be bright-cut as a pair.

What fun to speculate so!

Regards

Jan